On March 18, the leaders of the European Union reached a controversial deal with Turkey. That agreement, touted as a resolution to the refugee crisis, was in essence a cynical bargain to turn Turkey into a buffer zone. Turkey has agreed to act as a giant refugee holding center, keeping the millions of migrants fleeing conflict in the Middle East from reaching Europe and accepting those sent back from Greece. In exchange, the EU will pay Turkey three billion euros on top of the three billion pledged last November to help care for the refugees. It will also speed up the approval of visa-free travel to Europe for Turkish citizens and revive stalled negotiations over Turkey’s accession to the EU. The EU also agreed to settle a limited number of Syrian refugees—up to 72,000—directly from Turkey to Europe based on a crude “one-in, one-out” trade: for every Syrian smuggled to Greece but returned to Turkey, the EU will legally resettle one Syrian directly from Turkey to a European country. Finally, European leaders promised that once the flood of migration has abated they will implement a “voluntary humanitarian admission scheme,” a vaguely conceived program under which a coalition of willing member states could volunteer to resettle additional refugees.

Rights groups and refugee advocates, such as Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, have denounced the deal as immoral and illegal. Yet in the face of this unprecedented crisis, the deal might be defensible if it actually promised to shut down the smuggling operations that have led to thousands of refugees drowning and to prevent the collapse of the Schengen area—the 26-country border-free zone in Europe. But this deal will do neither. As the Financial Times columnist Wolfgang Munchau put it, “The EU not only sold its soul that day, it actually negotiated a pretty lousy deal.”

WHAT WERE THEY THINKING?

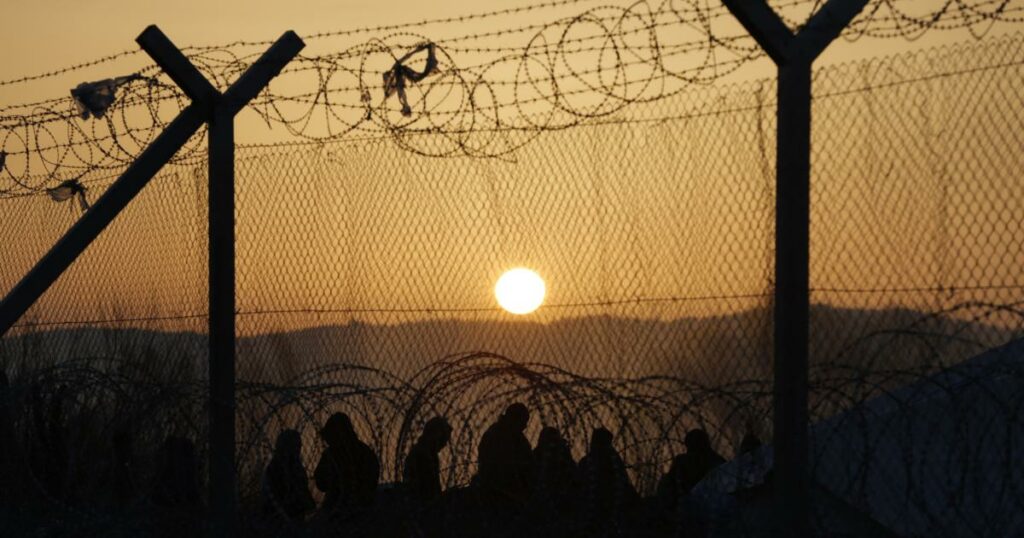

In the lead-up to the deal, the EU was under enormous pressure to cut the flow of migrants into Europe. Forecasts predicted the arrival of up to three million in the EU this year, the bulk of them passing from Turkey to Greece. And those countries that had been the most receptive to refugees, such as Germany and Sweden, had become less welcoming, especially after last year’s terrorist attack in Paris and a mass sexual assault in Cologne, Germany, on New Year’s Eve, the latter allegedly by groups of immigrant men. European publics were already calling on their leaders to shut the gates (and those cries will get even louder now in the wake of the Brussels bombing). Throughout the winter and spring, one state after another has reintroduced border controls, at least temporarily dismantling the Schengen area. In early March, Austria and Balkan countries shut down the Balkan route that most refugees had taken toward northern Europe, leaving nearly 50,000 trapped in Greece in deplorable conditions, with thousands more arriving across the Aegean every day. As the situation became unsustainable, EU leaders sought a new agreement with their Turkish counterparts to stop the flow of refugees.

The deal’s stated goal was to close down the smuggling industry that, over the past year, has brought roughly one million migrants—many of them refugees from Syria—from Turkey to Greece on a dangerous sea journey. The thinking is that if refugees know they will be returned to Turkey if they are smuggled to Greece, they will not risk their lives to make the trip. As German Chancellor Angela Merkel said after the agreement was sealed, “When you embark on this perilous journey, you’re not only risking life and limb, but you also have very little prospects for success.”

Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu is welcomed by European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker (L) and European Council President Donald Tusk (R) during an EU-Turkey summit in Brussels, March 7, 2016.

Emmanuel Dunand / Reuters

Although European policymakers accept that the deal is imperfect and rife with challenges, many of them insist that it is a step in the right direction. On Friday March 18, European Council President Donald Tusk tweeted, “[The] agreement isn’t a silver bullet, but part of EU’s comprehensive strategy on migration.” European policymakers feel that with the Turkey deal and the closure of the Balkan route, they have taken a step back from the brink of the refugee crisis, which was unraveling the Schengen area and threatening the entire European project. The reality is that the deal is utterly unworkable for logistical, legal, and political reasons.

THE PITFALLS

The EU–Turkey deal was supposed to go into effect on March 20, only 24 hours after it was signed. But reality intervened on day one. The first step of the plan involved dealing with the migrants currently stuck in Greece and those still arriving. Rejecting asylum seekers without a hearing and forcibly returning them en masse to Turkey would have been a clear violation of EU and international law. So to give the deal at least a patina of legality, the EU insisted that all migrants in Greece be given an expedited asylum hearing and a right of appeal before being returned promptly to Turkey.

Unsurprisingly, Greece, which has been unable or unwilling to set up a working asylum system over the past two years, could not do so in a day. So on the first day of the new deal, Greek officials announced that implementation would be delayed at least until the EU sent the 4,000 officials (judges, case officers, translators, and border guards) it had promised to Greece to help with the processing.

Even with support, the EU Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker acknowledged this would be a “Herculean task.” But Hercules was strong and the Greek state is weak. In its sixth straight year of economic crisis, much of it imposed by EU austerity and reforms, Greece likely does not have the means to coordinate thousands of officials. The task is even more difficult now that NGOs such as the UN Refugee Agency, Doctors Without Borders, and the International Rescue Committee pulled some of their support from the Greek islands to protest the transformation of certain refugee arrival points into detention facilities.

Even if Greece, with EU assistance, manages to process these claims and return refugees to Turkey, European courts may ultimately find the procedure illegal. Under EU law, migrants can only be returned to “a safe third country”—a designation that requires that the migrants not face risk of serious harm there, not be subject to forced returns to other unsafe countries (the non-refoulement principle), and that those granted refugee status be treated in line with the Refugee Convention. Although Greece may treat Turkey a safe third country, the European courts may not accept this. Turkey does not apply the Refugee Convention to refugees coming from countries outside of Europe and has a weak and rapidly deteriorating record on human rights. Although Turkey has spent roughly $9 billion supporting three million refugees, rights groups claim that many migrants in Turkey have been held in detention centers without access to legal counsel and that others have been forced back across the border to Syria. The Turkish government has stated emphatically that it will not change its current domestic legislation on refugees or allow for any EU monitoring to ensure Turkey meets the EU’s “safe third country” standards.

On top of that, the deal can be sustainable only if it succeeds in dramatically decreasing smuggling from Turkey to Greece. But Turkey has failed to crack down on the smugglers thus far, and it seems highly unlikely that Turkey will have a change of heart now. It is well known that refugee boats typically leave from Turkey to Greece very early in morning to avoid detection, but that the Turkish authorities do not start patrolling the waters near the island of Lesbos until 11 AM. This raises questions about the Turkish authorities’ real commitment to stopping the refugee trafficking. There was little sign of change on Sunday, March 21, the day after the deal was to take effect, when more than 1,600 people made the crossing from Turkey to Greek islands and four drowned. The flow of refugees to the Greek islands has slowed in recent days, but this is partly a result of high winds that made the journey too risky to attempt.

In addition to facing formidable logistical and legal hurdles, the deal generates perverse incentives, which will ultimately undermine it. For example, the goal of the deal is to sharply reduce the number of refugees crossing the Aegean illegally. But under the terms of the “one in, one out” scheme, Ankara is allowed to send one Syrian refugee to Europe only after it accepts a different Syrian refugee that has been returned to Turkey from Greece. This actually encourages the Turkish government to allow refugees to be smuggled to Greece. Further, even if the EU does resettle 72,000 refugees through this swap, there is no legal obligation for Europe to take more. Germany is hoping that it can lead a coalition of the willing to accept refugees voluntarily. But it has few willing partners. In September 2015, the EU pledged to relocate up to 160,000 refugees from Italy and Greece to other states in the Schengen area. So far, fewer than 1,000 of them have been resettled, as member states have accepted far below their pledged quotas or have refused to take any refugees at all—as Hungary, Slovakia, and now Poland have done.

The deal will also do little to deter refugees from seeking alternative routes. If you are one of almost three million refugees struggling in Turkey and you learn that only a tiny fraction will be granted asylum in Europe, you still have plenty of reason to take your chances with smugglers. If the Balkan route shuts down completely, smuggling rings and refugees will find lengthier and more dangerous routes, such as through the Caucasus and Ukraine, or over the Black Sea through Bulgaria and Romania. This month has already seen a spike in the number of refugees traveling to Italy via Libya, and the EU won’t be able to sign an agreement involving refugee returns with a failed state.

THE FAILURE OF MEMBER GOVERNMENTS

If European leaders believed that this deal would be a major step forward in solving the refugee crisis, they were deluding themselves. The EU–Turkey deal will most likely fall apart over the course of its implementation. European leaders will then be forced to go back to the drawing board. When they do, they will need to confront some inconvenient truths about what it will take to resolve the refugee crisis and to preserve free movement within Europe.

For one, bribing Turkey to act as a buffer zone between Europe and the Middle East may be tempting, but it is no substitute for constructing an effective common European border control and asylum policy. To be sure, the EU has put in place a Common European Asylum System and has an agency to coordinate and support enforcement of the external borders, known as Frontex. But implementation of EU asylum rules by member states collapsed when the refugee crisis emerged in 2015 and Frontex lacked the capacity and authority to intervene as needed. Many may be tempted to blame Brussels for these failings, but again and again it has been member state governments that have either blocked EU proposals designed to address the crisis or have agreed to new policies but failed to implement them.

By the end of 2015, the European Commission had opened 75 cases against 19 EU member states for violating EU asylum laws. Member states had openly flouted the Dublin Regulation, for example, which held that asylum seekers should be received and processed in the first EU country they entered. Greece and other states along the Balkan route had ignored the rules, letting migrants journey on to northern Europe. Merkel, with noble intentions, flouted the rules in a very different way. She announced last summer that she would welcome Syrians in Germany and would not send them back to the EU countries where they had first landed. Hungary has responded by building a border wall and holding sham trials—around 2,189 in the last seven months—convicting 99 percent of these migrants, many of them Syrian refugees, for “illegal crossings” and other border crimes.

A mounted policeman leads a group of migrants near Dobova, Slovenia, October 20, 2015.

Srdjan Zivulovic / Reuters

Other EU members have undermined the refugee relocation scheme, which promised to resettle 160,000 of the refugees in Italy and Greece to other states in the Schengen area. Hungary and Slovakia refused to participate and have brought legal challenges against the scheme, while other states have so far failed to accept their quotas. In the wake of last week’s terror attacks in Brussels, Poland’s government abandoned its earlier pledge to take in refugees. Finally, EU governments have neglected to deliver adequate staff to EU-sponsored “hotspots” for processing migrants in Italy and Greece.

CONFRONTING REALITY

Although there is no easy solution to Europe’s refugee crisis, EU member states’ shambolic response has worsened the situation. The deal with Turkey will, at best, slow or redirect the flow of migrants.

Faced with this reality, EU member governments have a choice to make. If the EU continues on its current path, the Schengen Area will further disintegrate as the temporary fences and border controls separating member states become permanent. The economic costs from the restricted movement will be huge, with estimates ranging from five billion to 18 billion euros ($5.6 billion to $20 billion) per year due to losses in trade, foreign direct investment, and tourism. The cost to European unity will be greater still. Migrants will continue to languish in squalid conditions in Greece, Italy, and elsewhere, causing immense human suffering and bringing shame upon Europe as a whole.

But if the EU member governments truly want to offer an effective response to the refugee crisis and preserve the freedom of movement within the Schengen area, they are going to have to significantly centralize control over their common external border and over asylum policy. The EU must press ahead with the establishment of a European Border and Coast Guard as proposed by the European Commission. To fund a real European Border and Coast Guard and make good on its pledge to improve the humanitarian conditions in Syria, the EU will have to mobilize considerable resources. Over the long term, new sources of revenue for the refugee crisis cannot come from voluntary pledges by member states, which ultimately may not be met. States that prove incapable of controlling Schengen’s external borders must seek EU support and, if necessary, temporarily allow the EU to patrol their borders. If they refuse, they are creating security risks for other states, and they should be suspended from the Schengen free movement zone.

States must also respect and enforce the EU’s common asylum rules. It is unfair and unsustainable for some states in the union, above all Germany, to welcome and support huge number of legitimate asylum seekers, while others, like Hungary, reject nearly all claims. If governments refuse to do their fair share, then, as the European Commission suggested when initially proposing the refugee relocation scheme, they should be forced to pay a fine to help finance care for refugees in the countries shouldering the burden. If they refuse to pay the fine, they too should be suspended from the Schengen area.

As European leaders dither with bogus solutions such as the deal with Turkey, the window for finding the right plan grows narrower. Let us hope that there is still some semblance of solidarity left by the time Europe recognizes the inadequacy of the deal and goes back to the drawing board to find a better arrangement, one that involves a common external border and asylum policy.

In the meantime, the EU must act quickly to alleviate the plight of the three million refugees in Turkey. The EU must follow through on its existing pledge to deliver three billion euros in assistance to Syrian refugees in Turkey and must put pressure on Ankara to make good on its promise to open its labor market to them. Until refugees in Turkey and elsewhere in the region can live in tolerable conditions and integrate socially and economically, they will continue to risk everything in the hope of reaching Europe.

Loading…

Source link : https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/europe/2016-03-29/europes-lousy-deal-turkey

Author :

Publish date : 2016-03-29 03:00:00

Copyright for syndicated content belongs to the linked Source.